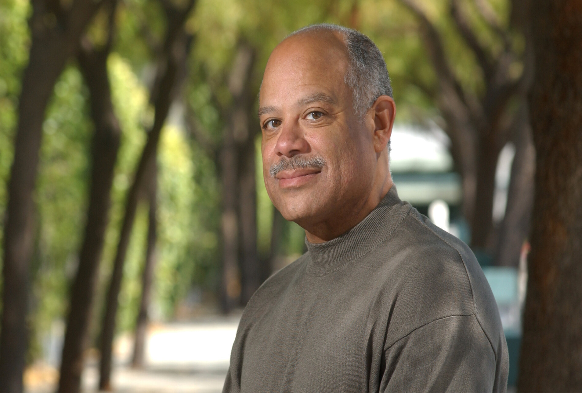

MARK E. DEAN

Is Mark Dean a computer scientist or is he an engineer? He surely is a tinker. As a boy, he and his father built a tractor from scratch.

Mark Dean’s grandfather was a high school principal, his father was a supervisor at the TVA (Tennessee Vally Authority) Dam. One of the few African American students attending his Jefferson City (Tenn.) High School, he was both a star athelete and a straight-A student. In 1979 he graduated at the top of his class at the University of Tennessee though he was actually a part of the university’s Minority Engineering Program.

After integration, he recalls, one white friend in sixth grade asked if he was really black. Dean said his friend had concluded he was too smart to be black.

“That was the problem — the assumption about what blacks could do was tilted,” Dean said.

That was the same bias Dean said he encountered when he first joined IBM, and a problem that has not completely disappeared.

“A lot of kids growing up today aren’t told that you can be whatever you want to be,” he said. “There may be obstacles, but there are no limits.”

Dean has been with IBM since 1980. Dean holds 3 of the original 9 patents on the computer that all PCs are based upon: Soon after joining IBM, Dean and a colleague, Dennis Moeller, developed the interior achitecture (ISA systems bus) that enables multiple devices, like modem and printer, to be connected to personal computers. Then he worked for a number of years before considering the doctorate.

Dr. Dean has said “when I was accepted at Stanford I had been out of school for ten years, so it was very difficult. I encourage people to go on to graduate school, but they should not wait as long as I did. It makes it very hard, But for me it was definitely the right thing to do and Stanford was the right place to do it. In hindsight, Stanford was the best choice because I already knew what I wanted to work on and both David Dill and then Mark Horowitz enthusiastically supported me in pursuing the research tropic I wanted to work on. The research I engaged in as a graduate student was very prudent, in that while some of the technology isn’t necessarily what we are doing today, it did allow me to better understand the best ways (pros and cons of certain approaches) to approach the development of processes. I came to Stanford with no knowledge of either circuits or processes, I knew logic design, architectures, bus interfaces and protocol, but I had no real knowledge of transistors, silicon processes and circuits. Stanford was my first exposure to custom circuits design to building things at transistor level. I am now managing a group focused on high-speed circuit design and I couldn’t have done it without the background I received at Stanford.”

He earned his Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering in 1992.

| In 1995, Dr. Dean was named an IBM Fellow in 1995, one of only 50 active fellows of IBM’s 300,000 employees. Dean was the first African American to be honored with IBM Fellowship.In 1997 Dean was Vice President of Performance for the RS/6000 Division and, along with his colleague Dennis Moeller, Dean was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame which has under 150 members. For inventing “a system that has allowed PCs to become part of our lives.”In 1999, as Director of IBM’s Austin Research Lab (in Austin, Texas), he lead the team that built a gigaherz (1000mhz) chip which did a billion calculations per second.In 2001 he was elected member of the National Academy of Engineers (NAE) .In 2004, Dr. Dean was selected as one of the 50 Most Important Blacks in Research Science. |

IDEA MAN

As one of IBM’s “idea men” he works independently on a host of pet projects, including the “electronic tablet.” :

Frustrated by the bulkiness of newspapers, Dean came up with the idea for a rugged, magazine-sized device that could download any electronic text, from newspapers to books. The device would also be a DVD player, radio, wireless telephone and provide access to the Internet. It would recognize handwriting (written directly on the screen), be voice-activated and even talk back.

But while it could accomplish all of those things, Dean thinks the tablet could be produced cheaply enough so that every student could get one in lieu of books, and publications could give one to every person who buys a subscription. As far out as the tablet may seem, Dean said it could be available soon. “We are almost there. The only technology left to conquer is the display, we have the other pieces,” Dean said. “We will see it pretty soon — easily within 10 years.”

With technology, “if you can talk about it, that means it’s possible,” he said.